Small Wonder

Exploring Dominica, the little Caribbean island that could.

Originally published in Travel + Leisure, December 2013

“SEE WITH YOUR FEET,” Martha Cuffy tells us. We’re descending a steep jungle trail in broad daylight, barefoot by design. Roots and thorns dig into our arches. “Use your toes to find your way,” she says in a soothing tone, as the voice in my head says ow ow ow ow ow ow ow.

My wife and I have followed Martha to this dripping, dappled forest to take the waters, the mud, the air, the tropical sunlight—magical elements that Martha promises will “rejuvenate your souls and strip you of all pretense.” This sounds about right.

Finally we emerge in a clearing at the bottom of the ravine. Soft, painless earth squishes under our heels. We inhale the moist air and take in our surroundings. Down the hillside, a waterfall cascades over mossy rocks, flowing into natural and man-made pools: some ice-cold, some steaming hot. Ferns and vines creep down the cliff, as if intent on reclaiming this spot. I count roughly 8,000 shades of green, punctuated by orange (heliconia), purple (banana flowers), and vivid red (torch ginger).

We’re deep in the rain forest of Dominica, at a mineral spa and botanical garden called Papillote. On any other Caribbean island, these four acres of tropical gardens—with 81 varieties of orchid alone—would be a major deal. On Dominica, Papillote is just one more lovely place to spend an afternoon.

“Feel those healing vibrations,” Martha says as she leads us under the waterfall. Her velvety British accent makes this sound a bit less silly. Raised in East London, she worked in finance before shifting gears and traveling to India to study Sanskrit and yoga psychology. Five years ago she moved to Dominica, the birthplace of her parents.

Martha wears a pale-green wrap over her bikini and an intricately knotted headcloth à la Erykah Badu. In the shade of a fan palm, she rolls out a reed mat and proceeds to bathe, scrub, and massage us both back to full health—using sulfur mud from the pools, homemade coconut oil, and springwater ladled with a calabash shell.

While Martha’s outdoor “Primal Spa” course had sounded hokey on paper—it certainly does as I recount it here, by the cold light of a laptop—there’s something about Dominica that makes it feel perfectly natural: like, Of COURSE I’m going to slather myself in mud and open my third eye to the wisdom of Gaia! Of COURSE I’m going to do that!

Earlier in our visit we’d met a nameless explorer—I mean he had no actual name, by choice—who was hiking with only his Speedo and a pendulum, divining the island’s “humongous volcanic energy.” I laughed, of course. But by the time Martha sloughs us with her coffee-spice scrub, I’ve come fully around. Dominica has a way of relaxing the objectional cortex, silencing the inner crank, opening you to things your home self would call kooky. Of course, it doesn’t hurt that the setting is overwhelmingly gorgeous.

Dominica (do-mi-nee-ka) was so named by Columbus, who spotted the island off his prow one pleasant Sunday—Dominica, in Latin—in 1493. Already there: the Kalinago people, who called their mountainous home Wai’tukubuli, meaning “tall is her body.” Midway between Guadeloupe and Martinique, it is among the largest of the Windward Islands—“twice the size of Barbados,” everyone will tell you, “with only one-fifth the population.” Geologically speaking, it is the youngest island in the chain, still being formed by volcanic activity. Development, too, is fairly nascent.

“Everything you need to understand about Dominica—our economy, our culture, our history—begins with the topography,” says Lennox Honychurch, an Oxford-educated anthropologist and Dominica’s unofficial historian. This was the last Caribbean island to be colonized—by the British, in 1763. “Even then, most colonial rulers never made it to the other side of the island,” Lennox says. The interior and rocky eastern coast were so remote as to be nearly ungovernable, leaving the Kalinago and Creole cultures somewhat to themselves.

As late as the 1960’s, when Lennox was growing up, there was no direct road from Portsmouth to Roseau, the capital, 25 miles away. “You had to wake up at dawn, hail a launch, and spend five or six hours chug-chugging down the coast,” he recalls. Even as paved roads inched across the landscape, Dominica remained a challenge to explore. Tourism, accordingly, took awhile to find footing. “It only came about because the banana market was in decline,” Lennox says. “Not until the eighties did we have an official Ministry of Tourism.”

What all this means today is an astonishing purity and variety of landscapes: volcanoes, deep gorges, rivers and waterfalls, and the world’s second-largest hot spring, Boiling Lake. Nearly half of Dominica is rain forest, and about a third is national parkland. (You can walk the length of the island on the 115-mile Wai’tukubuli Trail.)

For the adventure-inclined, there’s just so much here. Yet for the average Caribbean tourist, remarkably little: no all-inclusives, no Margaritavilles, not even a gift shop at the airport. Small hotels and guesthouses haven’t kept up with nearby St. Lucia and Barbados. Factor in the difficulty of getting here (the island’s airstrip accommodates mostly prop planes, with no nonstop flights from the U.S.), and you see why Dominica has been an outlier, until now.

Gregor Nassief is helping to change that, albeit in a very small way. At the moment he’s nose-deep in a ylang-ylang tree, reminiscing about his Dominican childhood.

“My mother used to make her own perfume from these blossoms,” he says. Their scent takes him back to when he and his siblings played on the beach just downhill, when this was simply another pristine cove on Dominica’s northwestern coast.

The Nassiefs are well-known on the island: Gregor’s grandfather owned what became Dominica’s largest rum distillery; his brother, Yvor, was formerly the minister of tourism. Gregor himself is a successful entrepreneur, working mostly in Latin America. But it is Secret Bay—the boutique resort he opened in June 2011—that has become his passion project.

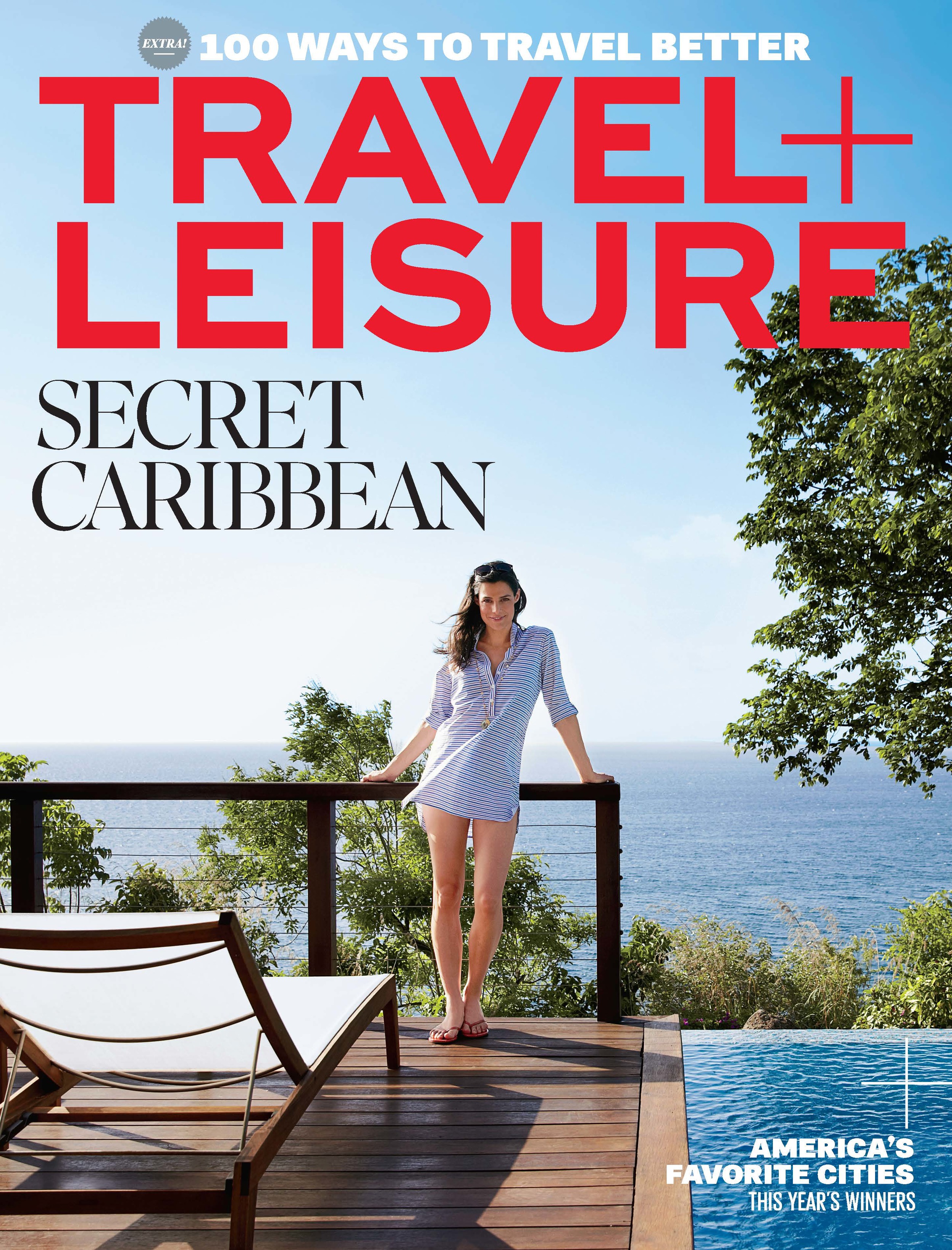

The resort sits on a promontory between two quasi-private beaches—one rocky, one white-sand and accessible only from the sea. Given the tranquil setting, Gregor wanted the buildings to keep a low profile: easy on the environment, easy on the eyes. For this he turned to celebrated Venezuelan architect Fruto Vivas, who happens to be Gregor’s father-in-law. Vivas’s design balances elegance and eco-friendliness as stylishly as any resort I’ve seen: six hillside and hilltop villas harken to Bali and Japan, with their hip-and-gable roofs, glowing hardwoods, and open-sided pavilions.

The standout villa, Zabuco 1, perches at the edge of a 110-foot cliff, with front-row views over the sea to Guadeloupe. The entire structure balances on four spindly concrete pedestals, which, according to Vivas, are strong enough to support a four-story hotel. The floating effect is magical. Downstairs is a deck with an outdoor shower and plunge pool fringed by bougainvillea. Upstairs is 1,400 square feet of indoor/outdoor living space: a sweeping deck and dining area; a kitchen and living room with floor-to-ceiling windows; and a bed-and-bath suite with a platform king, a freestanding tub, and enough closet space for a month’s worth of clothing—as if clothing were even necessary here. Best feature: a six-nozzle shower stall that slides open to reveal a dizzying view of the beach far below.

There’s a reassuring solidity to it all, from the immaculate ceiling joins to the heavy Swedish window hardware to the Guyanese greenheart timber. (The wood is so hard that nails will bend on it; thousands of holes had to be predrilled before construction.) All that effort paid off: this is no creaky-floored eco-camp with gaps between the screens. The design is luxurious in every way you want, and in none of the ways you don’t.

Equally unique is Secret Bay’s service model, more catered-villa than hotel: there’s no lobby, no bar, and no restaurant. Meals are taken in your suite, delivered by a dedicated attendant. Guests fill out lengthy questionnaires before arrival, so your fridge and pantry can be stocked with requested groceries. Kitchens have top-tier appliances, ample counter space, and plenty of proper cooking tools, from citrus squeezers to (hallelujah!) good sharp knives. Our wine fridge is filled with crisp, flinty rosé.

Cooking our own meals winds up being a highlight, given the ingredients Secret Bay’s kitchen provides (like fresh shrimp and snapper for our patio grill). From the garden outside we can pluck lemongrass and anise- and citronella-scented bay leaves. When we don’t feel like cooking, the chef prepares peppery fish soup, rich goat curry, and buttery grilled lobster.

One could easily spend two weeks holed up at Zabuco and never leave the premises. But the staff can organize anything from hiking to diving, fishing to birding, sailing to horseback riding—and Gregor, who seems to know everyone on Dominica, has a full roster of scholars, experts, and local guides on call.

If anyone really does know every soul on Dominica, it’s Bobby Frederick: town councilman, devout Rastafarian, community activist, veteran tour guide. Seeing the island with Bobby means slowing every 50 yards to greet another friend/neighbor/constituent.

“Ça cafette?”people call in Creole: Wha’ go on?

“Moi la, moi la,”Bobby hollers back: Me there, me there. This is standard greeting version 1; version 2 is to flash the thumb-and-pinkie shaka sign and shout, “Okayokayokayokay!”

We are driving through the coastal town of St. Joseph, an hour into our full-day tour, when Bobby decides we need refreshments—bush rum, to be precise. It is just past 10 in the morning.

He steers the SUV down narrow, twisting lanes and parks outside the Peacock Bar. We step from blinding sunlight into near darkness. “Okayokayokayokay!” someone bellows from across the bar. As our eyes adjust to the dim, we see Guiste, the owner, wearing a half-buttoned guayabera and the bawdy grin of a pirate. Greetings are exchanged. Guiste—rhymes with “feast”—pours us some of his house-made hooch: local white rum infused with aniseed. The licorice-y sting covers for the rough bite of alcohol. After a few sips, it’s actually kind of delicious.

Bobby and Guiste trade some rapid-fire patois, and our host procures a bottle of murky brown liquid, labeled LPA. “This’ll put boogie in your bones!” he says, pouring two shots for me and my wife. We taste—not bad. “What’s in it?” we ask. “Rum, prunes, and a stalk of marijuana,” Guiste fairly cackles. LPA, he explains, stands for Lever, Peter, à Terre—“That’s Creole for ‘Lift you up and throw you down.’”

Pleasantly boogie-boned, we push on down the coast, while Bobby recounts his peripatetic life story. He left Dominica in 1969 for college in Toronto, then lit out for Montreal, Vancouver, and Venice Beach, where he roomed with future Wailers keyboardist Tyrone Downe. Then to Oakland, where he owned a roller-skate-rental business called Disco Wheels. In the eighties, he traded California for Brixton, U.K. (“which I loved”), then traded England for Jamaica (“which I really loved”). Finally, in 1991, Bobby returned home, and hasn’t left the island since. He’s been too busy: opening an eco-guesthouse, winning his council post, running a nightclub in Roseau. Now he’s campaigning for national office, all while still leading island tours. Oh, and he also designed his own house.

“So you’re an architect?”

“I prefer the term artist. Some paint on canvas, I paint on land.”

We stop for a rare traffic light. Along the roadside, two shirtless guys with machetes are slicing coconuts in the back of a pickup. Bobby, of course, knows them both. We buy three the size of soccer balls.

Driving the length of the coast, we make it as far as Soufrière, a semi-charming village at the island’s southern tip. Frankly, there’s not much to see along Dominica’s western shore. It’s pretty, and relatively unspoiled for the Caribbean, but nothing you can’t find elsewhere. Inland, we’ll soon realize, is where the action is.

Bobby, however, is plenty engaging. Pointing to a vast new stadium in Roseau, he says, “The Chinese built that,” which prompts a digression about the PRC’s growing influence on Dominica. It was Chinese funding—and imported Chinese labor—that built the stadium, the State House, even the $100 million highway we’ve been driving on, he says. “But the road is already buckling! Our people would’ve done a far better job.” We pass a bunker-like complex adorned with Chinese flags. “That’s a dormitory for foreign workers—there are hundreds on the island.” And it’s happening across the region, he tells us. “The Chinese took over the Caribbean without firing a bullet. We were the lowest part of the fence, so they jumped right in.”

As the sun sets over a sparkling sea, we turn back north toward home. But first: one last stop. “Okayokayokayokay!” Bobby shouts as we pull up to a beachside rum shack.

The best of our excursions focus on the island’s dramatic interior—places like the Syndicate Nature Reserve, where we meet Dominica’s leading ornithologist for a morning hike. Bertrand Jno Baptiste, whom everyone calls Dr. Birdy, drives us 1,400 feet up a mountainside shrouded in clouds. With Birdy’s hefty telescope strapped to his back, we set off into the woods.

It looks like Endor up here. Massive gommier trees, circled by strangler vines, disappear into the mists above. Tiny hummingbirds hover around our heads, then dart off up the path. A gentle rain falls through the canopy. We pull our ponchos tight against the sudden chill.

At last, from across a meadow, we spot one: a Sisserou parrot, unique to Dominica, and the rarest of all Amazon parrots. Hanging upside down from a tree, feasting on white flowers, it is the most colorful creature I can imagine: an exploded paint factory of vermilion, emerald, aquamarine, and gold.

Later, on the drive out, Birdy points to a flagstone driveway cutting through a banana orchard. “An American just bought those nine acres for $35,000,” he says. My wife and I exchange glances. Gears are turning.

If you are a white female expat living on Dominica, it is safe to say you will grow dreadlocks. Yasmin Cole has been cultivating hers for three years now. A onetime professional rider from Norwich, England, she came to the island in 1999, built a tin-roofed cottage and stable in the forest above Portsmouth, and set up an equestrian camp and riding school called Brandy Manor. The name, Yasmin admits, is a bit of a joke; chickens run loose in the yard. “But I always fancied myself to the manor born,” she laughs.

The terrain here is well-suited for riding, and the Wai’tukubuli Trail passes right by her property. On sturdy St. Lucian Creoles we embark on a two-hour ride, led by Yasmin’s partner, Linton, a Rasta horseman in a rainbow tam. The first segment winds through fragrant bush. We duck under mango branches, weave among coffee shrubs, and stop for the occasional napping cow. A grapefruit tree grows through the hood of a rusted-out Chevelle. Linton plucks a plump yellow fruit for us to taste. He’ll do this continually as we ride—snapping off bay leaves (for brewing tea at the summit); prying open cacao pods (for slurping up the bitter-tangy pulp within).

Soon the forest falls away and we break into a gallop, racing to the crest of the ridge. Linton ties up the horses, and we take in a glorious view: in the far distance, past acres of green jungle, we see sailboats tacking across Portsmouth Harbor.

Back at Brandy Manor, Yasmin surprises us with a ripe mangosteen—our all-time favorite fruit, rarely found outside Asia. “I planted the tree a decade ago, and it finally fruited last July,” she says. There are also freshly laid eggs from her yard hens: a carton for us and a carton for Gregor Nassief. “He’ll never forgive me if I don’t send him these,” she says. “He’s become a bit obsessed with them.”

The next morning we understand why, when we scramble Yasmin’s eggs—silky, orange-yolked, delicious—with some leftover lobster, chiles, and herbs from Secret Bay’s garden. We have breakfast on the terrace, watching pelicans circle our cliff, then plummet into the surf. To our left, Secret Beach glows golden under a crystalline sky, while to our right, Tibay Beach is completely obscured by clouds.

“We have two microclimates here at Secret Bay,” Gregor had told us, “and this cliff sits right between them.” Indeed, all morning long, thick fog rolls over Tibay Beach. The rain forest above acts as a cloud confectionery, piping dollops of mist down the ravine to layer on the shore.

By noon the fog has finally lifted, and both beaches are drenched in sunlight. The cliffs of Guadeloupe come into view. After our 38th snapshot of a double rainbow, we put the camera away and hike downhill to borrow a kayak. An invigorating paddle takes us to Coconut Beach, an improbably tranquil half-mile of sand fronting the next bay over. On this resplendent afternoon in high season, we have the entire beach to ourselves, unless you count the hermit crabs.

Later, on our terrace, we join Trudy Prevost for a sunset yoga session. Trudy is a former computer systems designer from Vancouver who moved to Dominica “because of a powerful dream”; she now teaches yoga full-time. (And yes, she too has dreadlocks.) She leads her classes outdoors, “so you can really get the blue into your lungs.” With the calm voice of a friendly flight attendant, Trudy instructs us how to show our toxins to the exits.

“Feel that blue...Feel it seeping into your thighs...Inside your eyeballs...Swirling through your skull!”she says, while touching both toes behind her back. Seven days earlier I might have scoffed at this. But now I just smile, reach for my toes, and let the blue pour in. •

GUIDE

Getting There

To reach the island’s Melville Hall airport (DOM) from the U.S., you can fly through San Juan, Puerto Rico, or other neighboring islands, Antigua, Barbados, and St. Martin among them. From Melville Hall, either rent a car (you’ll have to drive on the left) or have someone from Secret Bay pick you up. It’s a one-hour drive to the resort.

Stay

secretbay.dm; five-night minimum.

Activities & Tours

Bertrand Jno Baptiste drbirdy@cwdom.dm.

Bobby Frederick rastours@digicel.blackberry.com.

Brandy Manor brandymanor@ymail.com.

Primal Spa Martha Cuffy’s wellness treatments. primalspadominica.com.

Rainbow Yoga rainbowyogaindominica.wordpress.com.

Terri Henry Excellent masseuse who does in-villa treatments for guests at Secret Bay. onelovelivity.com.