Hong Kong Now

Why Hong Kong—for all the naysaying—just keeps getting better.

Originally published in Travel + Leisure, October 2013

ON A LUSHLY PLANTED TERRACE high above the mad dash of Central Hong Kong, a Gatsbyesque bacchanal is fully under way. It’s a balmy May evening with threats of a downpour, but the humidity does little to quash the revelry. The verdant rooftop aerie, aglow with twinkling lights, feels like a secret garden floating above the city. That this opening party coincides with the launch of Art Basel Hong Kong—the first Asian edition of the global art fair—explains why so many gallerists, curators, and scruffy young artists figure among the crowd.

Duddell’s, the venue in question, is a curious mash-up: equal parts arts club, restaurant, gallery, and salon. With interiors by the British designer Ilse Crawford, the two-level space is deliciously, deliriously retro, as if you’ve stepped into the 1960’s Hong Kong of In the Mood for Love. You expect Maggie Cheung to sashay past in her cheongsam. The dining room serves classic Cantonese, and every detail is artfully executed, from the old-school tea service to the delicate har gau dumplings to the warbly jazz soundtrack. Throughout is an eclectic array of artworks: Chinese brush paintings; contemporary sculpture; rotating exhibitions in the upper-floor galleries. (This October brings a show curated by Chinese provocateur Ai Weiwei.)

Duddell’s also hosts lectures, screenings, readings, and performances, most reserved for members but some open to the public. “The idea is to build a community around art, not only for collectors and gallery owners but also for artists themselves. We want to be inclusive, not elitist,” says cofounder Yenn Wong. The 34-year-old Singapore-born entrepreneur has plenty of experience creating buzz: she founded JIA Boutique Hotels and owns four restaurants in Hong Kong, including 22 Ships, a new tapas bar from acclaimed London chef Jason Atherton.

Out on the terrace, Wong’s husband and business partner Alan Lo—an art-world player, property developer, and successful restaurateur in his own right—is reflecting on the tremendous, ongoing transformation of his hometown. “Ten years ago, what was there to talk about besides the culinary scene and retail?” he says. “Culturally, Hong Kong is far more interesting now. We have the international galleries, the alternative art spaces, a huge growth in collectors and the auction market. We’re still at an early stage, but in five years things will really be happening.”

Lo and Wong both speak of “a new heyday for Hong Kong,” and though they’re hardly impartial, something, inarguably, is in the air. The same restive energy that has galvanized the art community also courses through Hong Kong’s food, fashion, and design scenes. And it’s bubbling up in unexpected corners of town: in industrial zones turned creative hubs; in historic buildings being reclaimed and repurposed; and in neighborhoods defined not by outsize development but by improbable intimacy and grace. Yes, global brands and corporate heavyweights still dominate the terrain—but small, vibrant things now thrive in the spaces in between.

Duddell’s is nothing if not perfectly timed—a clever fusion of the city’s latest obsession (art) with its most enduring (food and drink). It’s also a canny hybrid of old and new, evoking the glamour of the mid 20th century in a place racing headlong into the 21st.

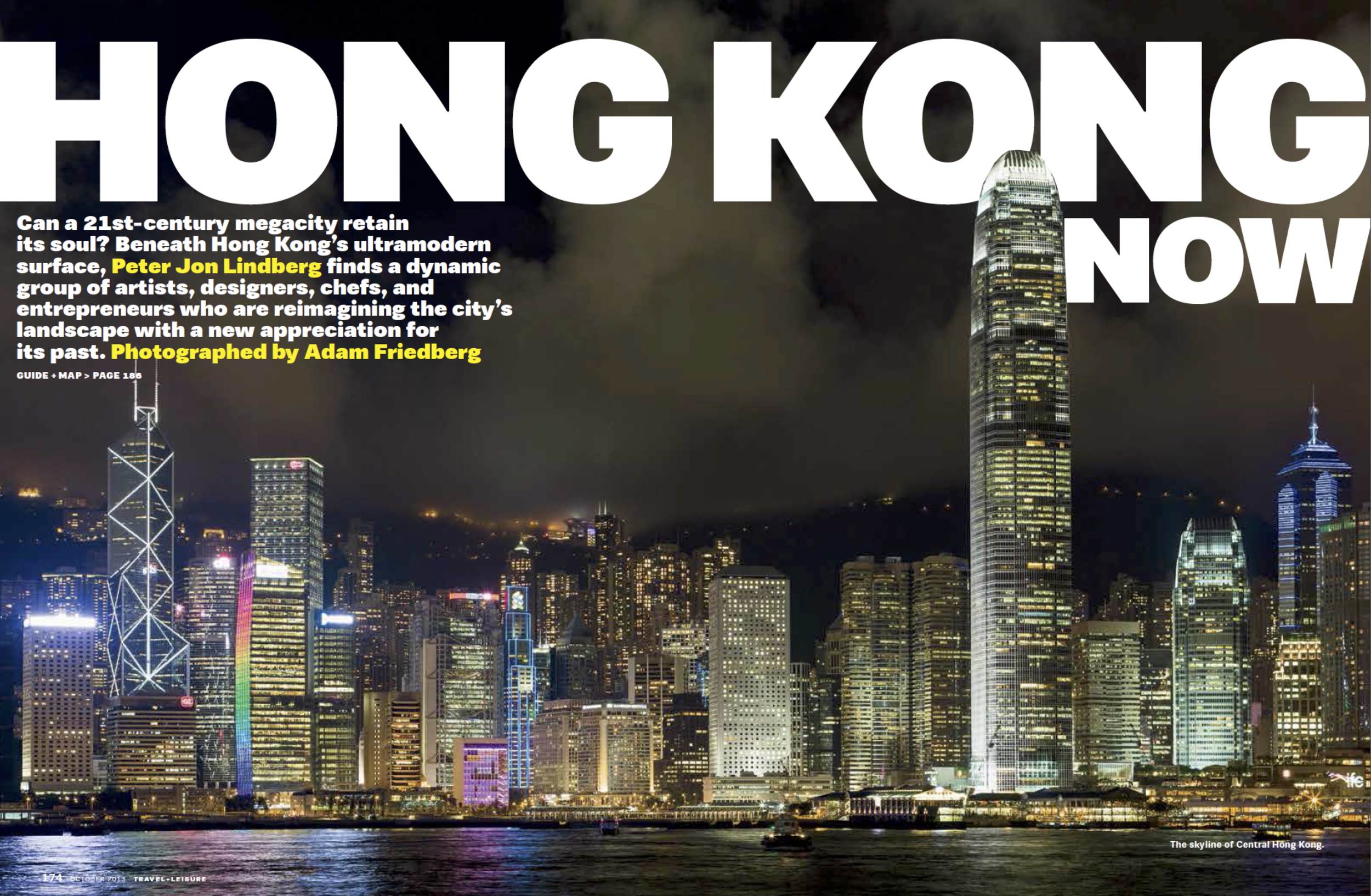

All great cities have their glory years, when their style and identity reach an apotheosis. Think of Paris in the 1920’s, Shanghai in the 30’s. Hong Kong’s golden age, certainly in terms of style and design, lasted from the 1950’s though the 70’s, when, amid an enormous boom in investment and immigration, the world rushed in and a new Hong Kong was born. The titans of finance and industry began erecting ever taller and splashier new headquarters, and the once humdrum skyline of Central was recast as an architectural showpiece. Many of Hong Kong’s most iconic buildings date from that mid-century heyday, including the old Bank of China tower (1950), a majestic study in Art Deco; Jardine House (1972), whose porthole windows give it the look of a ship plying the nearby harbor; and the Mandarin Oriental hotel (1963), which—at a staggering 27 stories—was once the island’s tallest building.

From the day it opened, 50 years ago this month, the Mandarin has been an emblem of Modern Hong Kong. Local residents have long treated the hotel as their living room, even if they’ve never spent the night upstairs. (Between the bustling lobby lounge, the salon and spa and barbershop, and the 10 restaurants and bars, everyone in town seems to pass through at some point.) Despite extensive renovations, the past remains present. With its boxy chandeliers, its retro tailoring shop, and its chief concierge in tails, the Mandarin still channels that James Bond glamour of the sixties—the same era that Duddell’s so skillfully evokes and that so many of us imagine when we think of “classic” Hong Kong.

But that sense of history is increasingly rare here. Too often, Hong Kong has forsaken its past—its architectural heritage most of all—in favor of relentless forward motion. Just witness the skyline of Central, where the Mandarin is now dwarfed by towers twice its size. “The attitude has been, ‘Why keep an old building when you can build a new one fifty stories taller?’” says John Carroll, professor of history at the University of Hong Kong, who was raised on the island. Perhaps because so much has been lost, more and more Hong Kongers—Carroll’s students among them—are interested in preservation. “A certain nostalgia for the colonial period has taken hold, especially among young Chinese, who of course aren’t old enough to remember it,” Carroll says.

Consider the case of Wing Lee Street, a 1950’s time capsule in the Sheung Wan district lined with colorful old tong lau tenement buildings, where shop owners live above modest storefronts. Three years ago this tranquil lane came under threat of redevelopment by Hong Kong’s powerful Urban Renewal Authority. Outcry ensued; protests were held—and, in a rare victory for preservationists, the URA called off the demolition, consenting to keep the historic tong lau façades. In a city that typically measures time by the pendulum swing of the wrecking ball, Wing Lee was a turning point, offering hope that at least some parts of Old Hong Kong might endure.

The inaugural Art Basel was a huge success, drawing 60,000 visitors and 245 galleries from 35 different countries. But the fair is just one (very big) piece in Hong Kong’s culture-capital ambitions. Last year the Asia Society opened its new headquarters inside a 19th-century explosives magazine built by the British Army, cunningly reimagined by architects Billie Tsien and Tod Williams. Nestled on a hillside above Admiralty, the bunker-like complex sets a dramatic stage for art, film, and cultural exhibitions—not least with its rooftop sculpture garden, framed by dense forest.

A mile west, the former Central Police Station (erected between 1858 and 1919, decommissioned in 2006) is set to become a nonprofit arts hub designed by Herzog & de Meuron. And a few blocks down Hollywood Road, the Police Married Quarters—two Modernist-era slabs that once provided housing for officers and their families—will soon be a hive of design workshops and performance venues known as PMQ. Meanwhile, major galleries such as Gagosian, Perrotin, Ben Brown, Lehmann-Maupin, and White Cube have opened outposts here. (Hong Kong is now the world’s third-largest art auction market after New York and London.) Even hotels are raising the bar. The muted oak-and-limestone interiors of the Upper House, designed by Andre Fu, form a gallery-like backdrop to a fine collection of contemporary artworks, including Hirotoshi Sawada’s Rise—an undulating steel waterfall clinging to a 100-foot-high atrium wall—as well as sinuous abstractions in brass by local sculptor May Fung-yi.

If art is putting Hong Kong back on the global map, it is also redrawing the cityscape itself. Just across the harbor, the $2.8 billion West Kowloon Cultural District is finally taking shape from a master plan by Norman Foster. The waterfront site will include a Chinese opera house, indoor theaters, outdoor stages, and the much anticipated M+, a museum of visual culture designed by Herzog & de Meuron and TFP Farrells. When it opens in 2017, M+ (as in “Museum Plus”) will be the most ambitious contemporary art space in Asia. (Its executive director, Lars Nittve, was the founding director of London’s Tate Modern.)

“M+ is a global museum with an Asian perspective, not simply an Asian museum—that’s a key distinction,” says Aric Chen, curator for design and architecture at M+ (and a former T+L contributor). Chen compares its place to Tate Modern, MoMA, and the Centre Pompidou, in that “You can tell where they are, but they’re not confined to where they are.” He expects M+ to add another perspective to a larger, international conversation, acknowledging that Asia “has been on the periphery of that conversation, until now.”

Chen dispels the myth that Hong Kongers only care about money. He cites the exhibition of inflatable sculptures curated by M+ and set up along the Kowloon waterfront. “We had 27,000 people turn up in a single day!”

This is clearly a watershed time for Hong Kong’s art scene, which Nittve has compared with that of Los Angeles a generation ago. Of course, there’s a difference between a lucrative art market and a vibrant community of artists—and the latter is what a handful of Hong Kongers are now working to develop.

Drive south along the expressway from Central Hong Kong to Aberdeen, past the Happy Valley racecourse and rows of unassuming high-rise apartments. Just beyond the tunnel, look left, and on a fourth-story terrace you’ll see a grove of bamboo, rippling in the breeze. Except that isn’t really bamboo, it’s an art installation—made of 346 bamboo tent poles—called The Industrial Forest. And that isn’t an apartment, but an artists’ space called Spring Workshop.

Spring functions as a nonprofit—mounting exhibitions, hosting events, and sponsoring residencies for local and visiting artists. Recent guests include Chinese artist Qiu Zhijie, whose installations play off the theme of maps, both real and imagined; and Indonesian performance artist Melati Suryodarmo, whose latest project entailed dancing in heels atop greasy blocks of butter (you should probably YouTube that).

The bamboo is a reference to the surrounding neighborhood: Wong Chuk Hang, meaning “yellow bamboo stream,” which once described this backwater on the far side of Hong Kong Island. During the last century, WCH evolved into a thriving industrial zone. Now many of its derelict factories and warehouses are being reclaimed by young creatives.

“What I love about Wong Chuk Hang is that you can see Hong Kong’s history, present, and future in one small neighborhood,” says Mimi Brown, an expat from Los Angeles who opened Spring in 2011. “You still pick up all these smells: the printing houses, the candle shops, ink from the stamp manufacturer.”

Brown had a career in music before moving to Hong Kong in 2005, where she became active in the city’s gallery scene. “But none of those spaces in Central really spoke to me,” she recalls. When she discovered Wong Chuk Hang, something clicked. “The vastness of the interiors, the high ceilings, the messiness of an industrial neighborhood—it gives you a psychological freedom,” she says.

With its designer kitchen and expansive terraces, Spring is more artists’ colony than traditional gallery. The intention, Brown says, is that “you don’t just come to view the art—you sit down afterward for a meal, have a drink on the terrace, and digest it all at a calmer rate.” Her fingers trace the border of one of Qiu’s conceptual maps. “I always left exhibitions hungry for more,” she says. “I wanted to linger, talk further, suspend myself a while longer before being cast back into the real world.”

In Hong Kong, the “real world” has typically meant hermetically sealed shopping malls, as vast as airports and chilly as meat lockers. But among the current generation, a newfound appreciation for organic street life is emerging. Alan Lo and Yenn Wong both rave about the tranquil enclave of Tai Ping Shan, tucked above Hollywood Road in Sheung Wan. A hilly tangle of shady lanes and frowzy low-rises centered around a banyan-shrouded park, the neighborhood feels a bit like Asterix’s Gaulish village, still holding out against the Romans. Laundry hangs from bamboo poles. Sidewalks see more xiangqi games than Ferragamo heels. Storefronts are mostly given over to junk shops, coffin dealers, and tailors selling clothes for corpses. (Tai Ping Shan has long been the center of Hong Kong’s funeral trade, which has helped ward off superstitious developers.)

Lately, the neighborhood has also become quite the hipster scene. Some even insist on calling it “Poho,” after its main thoroughfare, Po Hing Fong. “Only two years ago it was this sleepy, forgotten place,” Lo recalls. Now it’s full of energy: teahouses, design shops, galleries, nonprofits—or what Lo and Wong call “pockets of soul.”

One of those is Po’s Atelier, an ace new bakery run by a Swede and a Hong Konger that was retrofitted from a 1950’s garage. Next door is its sister coffee shop, Café Deadend, serving breakfast until noon in a courtyard fringed with rosebushes. It was here one morning that I met Fiona Kotur, the New York–born, Hong Kong–based designer of Kotur handbags. She’s a regular at Po’s, as her studio is two blocks away.

Kotur and her husband moved to Hong Kong when he was transferred for work. “We thought we’d come for a year or two,” she recalls with a laugh. “That was 2002.” Two years later she started Kotur. In the decade since, the fashion world has fallen for her clutches, minaudières, and day bags—and Kotur, meanwhile, has fallen hard for Hong Kong. “There’s tremendous optimism here, a sense of excitement about what’s next—arguably more so than in New York,” she says.

Working with brocade, crystal, metallics, and skins, Kotur’s designs tend to reference bygone eras, from 1930’s Art Deco to 70’s disco glam. I ask if that element of nostalgie was inspired by Hong Kong. Quite the opposite, she tells me. “Because Hong Kong is a very forward-thinking place, people don’t tend to look back,” she says. “You don’t inherit old jewelry, for fear of bad spirits. Antique furniture isn’t passed down. And vintage clothing doesn’t have much cachet. Hong Kongers are very current; they dress on-trend. Traditionally, old things aren’t seen to have value. And old buildings…well, heritage preservation is quite new here.”

Which, she adds, is why Tai Ping Shan appeals: the age, the grit, the indie cafés and boutiques. “The neighborhood still has balance,” Kotur says as we descend a crumbling staircase toward Hollywood Road. “There’s birdsong in the morning, people doing tai chi in the park.”

A similar indie spirit is upending Hong Kong’s restaurant scene. Where big, splashy productions once ruled the game—places like Zuma, the swank Japanese restaurant in the Landmark shopping mall—small-and-scrappy upstarts are now all the rage. Prime example: Yardbird, the wildly popular yakitori joint opened two years ago by chef Matt Abergel (who previously ran the kitchen at Zuma).

This spring Abergel unveiled his follow-up, Ronin, where the focus is on impeccably prepared seafood. Hidden behind an unmarked door in Central, Ronin has just 14 stools set along a Japanese kiaki-wood countertop. Marley’s “Natural Mystic” lilts over the stereo. In contrast to rowdy Yardbird, Ronin is decidedly more grown-up, with sleek, minimalist décor (go ahead and call it “Zen-like”). Most eye-catching feature: a wall of 90-odd Japanese whiskeys behind the bar, glittering like an altar. The drinks program—which also leans to rare shochus and artisanal sakes—is overseen by Elliot Faber, who grew up with Abergel in their native Calgary. As at Yardbird, the food reflects Abergel’s mastery of Japanese techniques and nuanced flavor combinations. A luscious Shigoku oyster is cleanly dressed with red-shiso-infused rice vinegar, to mouthwatering effect; lightly pickled mackerel needs only a wedge of tart persimmon to offset the oils and coax out the fish’s sweetness.

You’ve got to love a city where two Canadian Jews can hit it big with yakitori. But Abergel and Faber are more rule than exception in this singularly cosmopolitan town. Life in Hong Kong transcends cultural and culinary borders, such that nothing is truly foreign and nothing doesn’t belong. Is it surprising that this is the only place on the planet where you can eat raw oysters from six continents?

Of course, that’s long been the case. Hong Kong’s many years of dual citizenship—and its role as a capital of global capital—made it a uniquely “post-national” city, belonging to no one and everyone at once. The cityscape itself came to reflect this: shooting ever-skyward to float above the earth, untethered by physics or geography. (Today, via Hong Kong’s endless elevated passageways, you can walk for miles and never touch the ground—and if you do, it’s probably landfill.)

The current population is actually far more homogeneous than you’d think: 94 percent of Hong Kongers are of Chinese descent, with Westerners accounting for only a fraction of non-Chinese residents. Yet while the international community is small on paper, it plays an outsize role in practice. (During my visit, half the city seemed to be celebrating Le French May, a monthlong festival of Gallic culture.) “This is a Chinese city—it’s not like New York, which is very multiracial and multicultural,” Kotur says. “But Hong Kong is still extremely international in its outlook.”

It is also extremely transient. Among Hong Kong expats, the assumption is that everyone’s just passing through. (As a local friend told me, “Whenever you meet someone, the first question is, ‘So how long are you here?’”) But if anything, that sense of impermanence has inspired a stronger attachment to the things that have endured, and that seem to mean more with each passing year. Things like the Mandarin’s throwback barbershop, still looking like the Beatles might pop in for a shave. Or the impossibly skinny double-decker trams that still jangle down Des Voeux Road. Or the beloved Star Ferry, founded in 1880, still puttering across an unrecognizable harbor, linking the island to Kowloon and Hong Kong’s future to its past.

For decades it was imagined that Hong Kong’s best days were behind it—that it had become too big, too cold, too dismissive of its inheritance. But while it may not be the first or even the fourth visible layer in the palimpsest of the city, the past is there, giving Hong Kong an indeterminate depth that so many 21st-century megacities lack. History swirls through this town like a whiff of incense curling up from a temple altar, or a spiraling hawk glimpsed from your 80th-floor window. And the golden age? Beneath all that lucre, between those lofty high-rises, Hong Kong’s golden age may have only just begun. •

GUIDE

Getting Around: Hong Kong’s metro system is surprisingly easy to navigate, with signs in English throughout. Taxis are cheap and plentiful, but be sure to ask your concierge to write your destination in Chinese before hailing.

Stay

Mandarin Oriental, Hong Kong: Connaught Rd., Central; mandarinoriental.com.

Peninsula Hong Kong: An institution since 1928, the Pen has old-world flourishes (Rolls-Royce fleet; pillbox-wearing pages) and ultra-high-tech rooms. Salisbury Rd., Tsim Sha Tsui, Kowloon; peninsula.com.

Upper House: This intimate retreat perched atop the JW Marriott has the excellent Café Gray Deluxe restaurant (from chef Gray Kunz), a stylish bar, and, refreshingly, no shopping arcades or bustling lobby scene. Pacific Place, 88 Queensway, Admiralty; upperhouse.com.

Eat

Ammo: Inside the new Asia Society Center, this showstopper has soaring ceilings, Deco details, and a huge wall of windows onto the surrounding forest—plus a sensational sea-urchin-and-tomato pasta. Asia Society Hong Kong Center, 9 Justice Dr., Admiralty; asiasociety.org.

Duddell’s: 1 Duddell St., third floor, Central; duddells.co.

Po’s Atelier & Café Deadend: 70 & 72 Po Hing Fong St., Sheung Wan; posatelier.com.

Ronin: 8 On Wo Lane, Central; roninhk.com.

Ta Pantry: Private Dining French-trained chef (and former model) Esther Sham recently moved her acclaimed private kitchen to a larger space near the harbor. Sea View Estate, Block C, fifth floor, 8 Watson Rd., North Point; ta-pantry.com.

22 Ships: 22 Ship St., Wan Chai; 22ships.hk.

Yardbird: 33-35 Bridges St., Sheung Wan; yardbirdrestaurant.com.

Do

Asia Society Hong Kong Center: 9 Justice Dr., Admiralty; asiasociety.org.

Kotur: Hollywood Centre, second floor, 233 Hollywood Rd., Sheung Wan; koturltd.com; by appointment.

Para Site: After 17 years, Hong Kong’s most celebrated contemporary art space is still the epicenter of Sheung Wan’s gallery scene. 4 Po Yan St., Sheung Wan; para-site.org.hk.

Spring Workshop: Remex Centre, third floor, 42 Wong Chuk Hang Rd., Aberdeen; springworkshop.org.