Israel Food Tour

From Tel Aviv to the Galilee with Michael Solomonov, devouring his homeland

Originally published in Saveur, January 2016

“Bro, check out these crazy fucking squash!”

Mike Solomonov, sneakers caked in mud, hands stained red from plucking mulberries, comes bounding across the field like he’s just picked the padlock on the candy shop. He carries a long, pale green vegetable resembling a peeled cucumber, albeit layered in downy peach-like fuzz. It’s a fakus, he tells me, a curious plant native to this part of Israel. “You can cook it like zucchini, or eat it raw like cucumber,” he says, breaking off a chunk and offering me a bite. It’s snappy, slightly bitter, and entirely delicious. “Right?!” the chef replies with a grin, sprinting back to the patch to harvest some more.

We’re at Mizpe Hayamim, a mountaintop farm and wellness retreat overlooking the Sea of Galilee. Most people visit Israel for the history, the monuments, but we’re here to ogle and devour as much food as possible. To that end, all morning we’ve been prowling Mizpe Hayamim’s fields in the summer heat: chomping into sun-warmed tomatoes, nibbling uprooted leeks, slicing tart green plums to sprinkle with fresh za’atar.

Every 38 seconds Solomonov leaps up to announce a thrilling find in the dirt—show him an obscure specimen of produce and he’ll tell you its provenance, flavor profile, and ideal preparation. He waxes rhapsodic about the robustness of sautéed mallow, a.k.a. Egyptian spinach, or about the baby eggplants grown in Israel’s north: “They’re tiny, the size of Tic Tacs—unbefuckinglievable!” (Solomonov talks about vegetables like other Philadelphians talk about the Eagles.)

At the edge of the farm there’s a rusted wire fence, and beyond that a hostile expanse of scrub and shale—a reminder that all this green bounty is the work of man. As emblems of Israeli agricultural ingenuity go, few can compare to this impossibly lush farm in the desert.

Solomonov was born just 80 miles from here, in the village of G’nei Yehudah, outside Tel Aviv. His family moved to Pennsylvania when he was 4, and though he’s spent most of his life in the States, he feels utterly at home in this landscape: picking za’atar and eggplants and mulberries and fakus, conjuring some tasty way to turn them into dinner.

If you’ve been to Zahav, Solomonov’s Israeli-inspired restaurant in Philadelphia, you’ll know about his coffee-braised brisket, his grilled duck hearts, his smoked-and-braised lamb shoulder with pomegranate and Persian rice. But mostly you’ll remember what might elsewhere be considered mere accompaniments: the Moroccan spiced carrots, the beets with tehina, the twice-cooked eggplant, the pitryot hummus scattered with hen of the woods mushrooms, the fried cauliflower … good Lord, the fried cauliflower. That the cauliflower rivals the lamb as his signature dish is testament to the chef’s genius with vegetables, which become in his hands as id-fully craveable as any slow-cooked, fat-laced protein.

“In Israel, vegetables are not an afterthought,” Solomonov writes in his new cookbook, Zahav: A World of Israeli Cooking. “In Israel, vegetables are the whole thing.” Last summer I joined the chef on a return trip to the homeland, to learn firsthand how that whole thing played out.

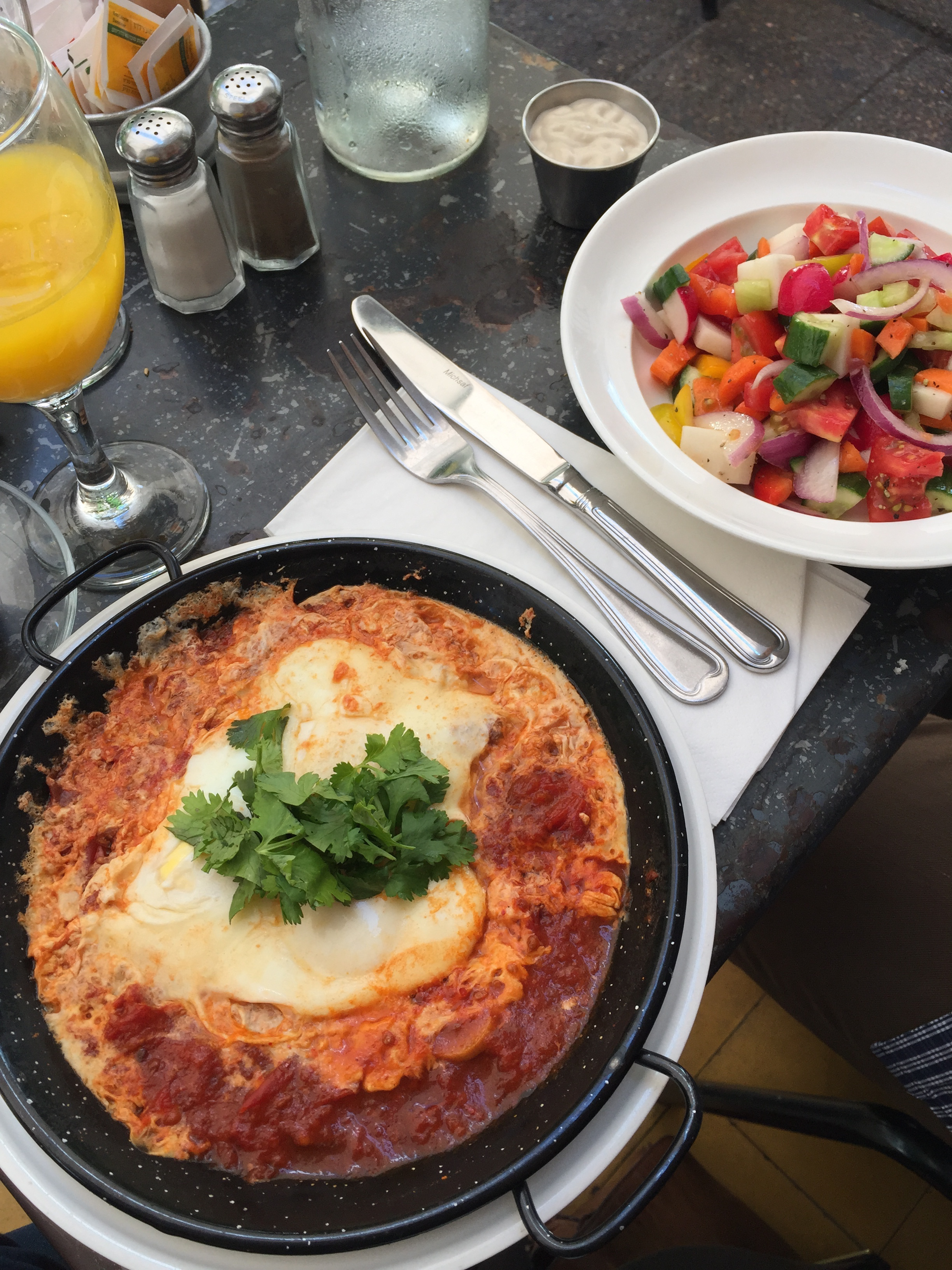

To visit Israel with Solomonov is to eat lustily, impulsively, and nonstop, bouncing from one hummusiya or laffa cart to the next. The chef has the build, demeanor, and close-cropped hair of an athlete, and the energy of a jackrabbit. He’s up at sunrise to surf the breaks off Tel Aviv’s Gordon Beach. Afterward it’s a sprawling Israeli breakfast spread at our hotel—and then we’re off on a manic, multi-culti food crawl as we tag all the dishes on Solomonov’s must-eat list.

“There are no ‘Israeli’ restaurants in Israel,” he says. “Instead you have Bulgarian, Iraqi, Czech, Turkish, Romanian, Tunisian, and a few dozen other cuisines all happening in this one tiny country.”

This becomes clear on our first night in Tel Aviv, when we meet friends at a 1950s-era Yemenite shipudiya (grill house) called Busi, a longtime favorite of Solomonov’s. “These guys do amazing cow udders,” he assures us as we take our seats at a long booth. Within minutes, servers have set down dozens of small plates, lined up end to end—a runaway train of salatim spanning the length of the table.

“They call this place a Yemenite grill, but the food is from all over,” he says, pointing his way around the salatim spread. “These are Moroccan”—a carrot salad with Aleppo pepper and cumin—”this is Russian”—a mayonnaise-y pea-and-potato dish—”this is North African”—tomato-and-pepper stew. “The coleslaw is Polish, the baba ghannouj is Turkish or Greek, the pickled cabbage is German, and that pepper salad, I don’t know where that’s from but it’s stupid-good.”

Starting a meal with a round of salatim or salads—traditionally a Palestinian thing—is now a given at most restaurants here. And this is no throwaway filler to tide us over, but a meal’s worth of flavors in itself, Israel on a single overcrowded table. All those tastes somehow fit together, with one dish coaxing out latent notes in the next. Solomonov begins dinners at Zahav the same way, with a cluster of starters that feel like the main event. At Busi, as at Zahav, one could leave after the salatim and feel entirely satisfied.

Fortunately, we don’t leave—and now come the meats and offal, straight off the grill. Cow udders are no longer on the menu, their kosher status having recently been questioned by rabbinical authorities. (Only Solomonov seems disappointed by this.) But there is fabulous grilled onglet; flame-licked sweetbreads; grilled foie gras dangling off the skewer like molten marshmallows; and, best of all, crunchy-tender umami-bombs that I presume are chicken kidneys until he corrects me: They’re turkey testicles, and they’re gone in seconds.

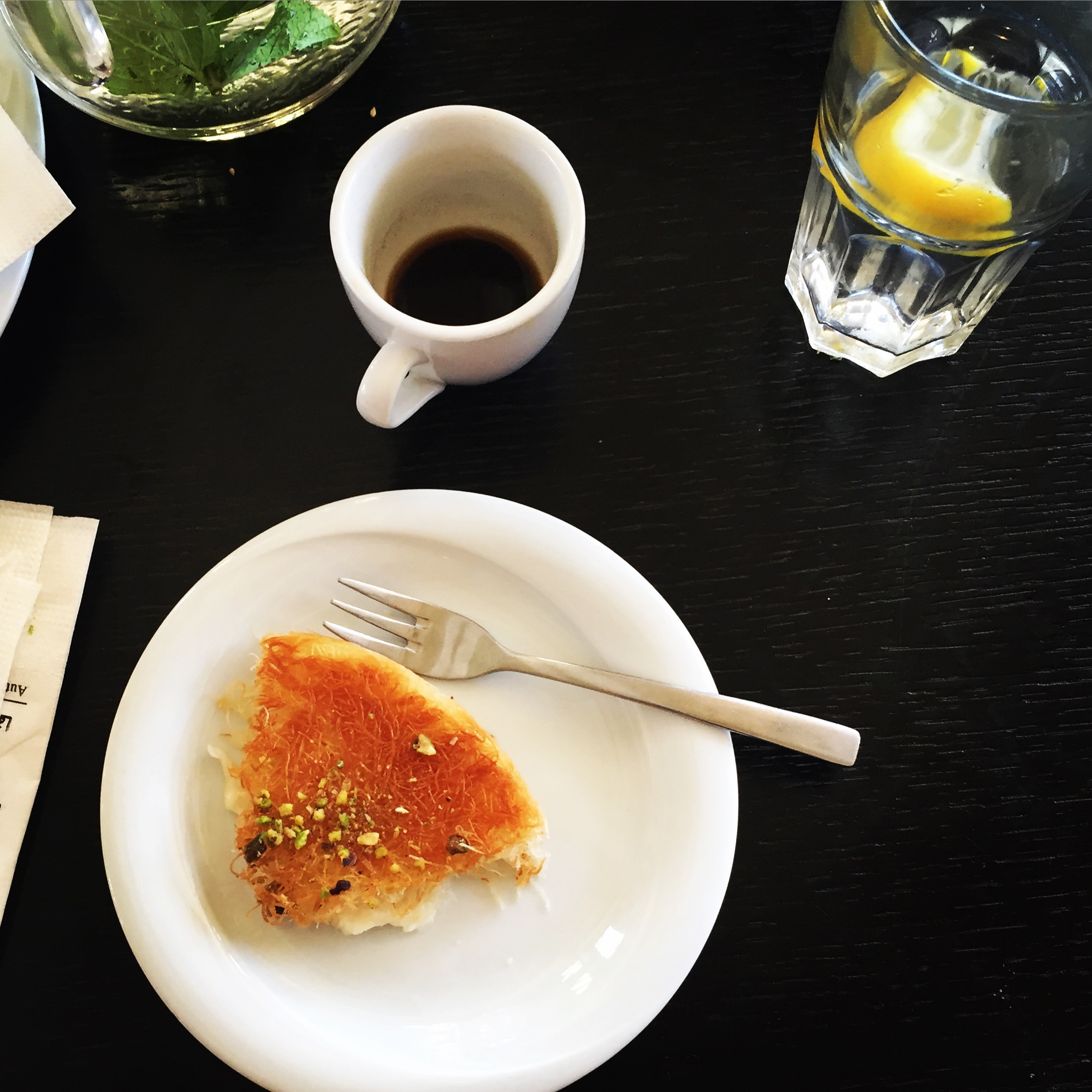

After dinner there will be more stops for snacks—including the phenomenal roasted cauliflower at Miznon—followed by a midnight round at Ramleh, a jam-packed drinking den off Rothschild Boulevard. Behind the bar, the staff is mixing cocktails while grilling molasses-topped apricots over charcoal. (Does your local do that?) Everyone is dancing madly and urgently singing along. “Israelis throw down like nobody else,” Solomonov shouts over the roar. “You get to a party at seven and some girl’s already drinking vodka from a ram’s horn.”

Before he got famous for hummus and fried cauliflower, Solomonov held the food of his homeland at arm’s length, at least professionally. In today’s post-Ottolenghi era, it’s easy to forget when Israeli cuisine was not taken seriously by the chef-world elite, or even by its own practitioners. “In America, ‘Israeli restaurant’ meant divey places serving crappy shawarma or falafel,” Solomonov recalls. “They were owned by Israeli businessmen who were neither chefs nor grandmothers, so the food sucked.”

That low standard, he says, informed a certain bias against Middle Eastern flavors, which chefs and diners alike saw as both too simple and too exotic, at once over-familiar (falafel, pita bread) and confoundingly strange (preserved lemon, chicken hearts). “When I started out in restaurant kitchens, I didn’t think hummus or a chopped salad could ever be cool,” he says.

Zahav was an outlier when it opened in 2008—a high-end Israeli restaurant in Old City Philadelphia—but became an unlikely hit, earning Solomonov a James Beard Award. Embracing the dishes he craved at home (and on his return visits to Israel), the chef came to realize that “those simple, elemental foods and flavors are what we all want, if done right.”

Take, not least, that hummus. So beloved is Zahav’s rendition that in 2014 the chef opened a spin-off, Dizengoff—named for one of Tel Aviv’s main boulevards—dedicated wholly to hummus. (He has since opened a second location in New York.) As Solomonov notes in his cookbook, the hummus has just five main ingredients, “but it took us longer to develop than any other recipe.” The key, he says, is “an obscene amount” of tehina, made daily with organic sesame seeds, lemon, and garlic, which results in a far lighter and nuttier hummus. (Another rule: Hummus never spends a second in the fridge.) Simple as it is, the dish can also be dressed up—ladled with stewed favas (ful), with spicy ground beef and pine nuts (Jerusalem-style), or, in the classic masabacha preparation, with warmed chickpeas and a generous drizzle of olive oil.

One of the best masabacha hummus preparations I’ve tasted (with Zahav’s running a very close second) is served at Shlomo & Doron, an indoor-outdoor, communal-seating hummusiya in Tel Aviv’s Yemenite Quarter, down a narrow lane from the Carmel Market. Purportedly founded in 1937, it also offers what the menu calls a “complete” hummus: piled with ful and simmered chickpeas, minced garlic, schug (a cilantro-spiked Yemenite hot sauce), fresh parsley, and—because you need it—a boiled egg. The absurdly rich assemblage of textures and temperatures recalls an ‘80s-era nine-layer dip; you scoop it up with fluffy, piping-hot pita or (better yet) wedges of raw, sweet, fiery white onion. Every ingredient blasts through with piercing freshness and intensity, which, as Solomonov points out, is what distinguishes dishes in Israel from the same ones back in the States.

“Israel is basically an island,” Solomonov says as we browse the produce bins in the Carmel Market, admiring the plump dates, neon-green kiwis, and countless varieties of eggplant. “Everything comes from here, and it’s not a big country, so it never travels far. You’re eating cucumbers that have never seen a fridge or the back of a truck, at least not for long. And avocados from a kibbutz that’s minutes away.”

He tells me about the tomatoes grown in the Negev desert, near Jericho. “Like everywhere, they’re running low on water, so they built this giant aquifer, which they use to grow tomatoes, melons, olives, all this stuff. But the water is brackish, and that salt translates into added sugar in the fruit. The tomatoes are so sweet they taste like Coca-Cola.”

Good tomatoes, of course, are available year-round in Israel. But Solomonov cooks in Pennsylvania, where for a third of the year hardly anything grows above ground. How do you bring the fertile Middle East to the frozen Mid-Atlantic? For the chef, it’s about substitutions. Consider, for instance, the Israeli salad (which Israelis actually refer to as a chopped or Arabic salad)—diced tomatoes, cucumbers, and onion dressed with olive oil and parsley. “There’s no meal where Israeli salad would be out of place,” Solomonov says. During visits to the homeland he’ll eat it three times a day. But during frigid Pennsylvania winters, he’ll swap in mangoes, grapes, Asian pears, or pickled persimmons for the tomatoes. It’s hardly locavore, but it is seasonal, and it’s fantastic. “The point is not to get hung up on specific ingredients,” he says, “and just respect that balance of sweetness and acidity and textures.”

“Fried eggplant, man—it’s like good French toast, sweet and savory and totally delicious,” Solomonov says en route to our final meal in Tel Aviv. This is a man who can do more with eggplant than most chefs can do with a chicken. At Zahav, he’ll sear thick meaty rounds until nearly blackened, then top them with tehina, carob molasses, pistachios, and pomegranate seeds. He’ll grill one whole until it collapses into a creamy pudding, then dress it with herbed labneh, grilled tomatoes, and pea shoots. Or—in his favorite method—he’ll roast it directly on the coals, turning the skin to charred parchment and perfuming the flesh with sweet smoke. (He always brines eggplant before grilling, to mitigate the bitterness.)

But it’s sabich, the fried-eggplant sandwich introduced to Israel by Iraqi Jews, that Solomonov hungers for as soon as he lands in Tel Aviv. Traditionally eaten on Saturday mornings, it happens to be a knockout remedy for hangovers and long-haul flights.

So here we are in suburban Givatayim, just north of Tel Aviv proper, on a side street lined with fiery orange poinciana trees, and although it’s barely 11 a.m., the line is out the door at Oved’s Sabich. As we wait, three ponytailed women—IDF camouflage, machine guns slung over their shoulders—stand at a Formica countertop, inhaling their sandwiches in a minute flat.

Finally we reach the front, order two for ourselves, and watch the line cook set to work. It starts with thin coins of eggplant that are brined, fried low-and-slow in canola oil, and left to cool; their appearance and mouth-feel recall Caribbean fried plantains. Into a fluffy pita they go, then on goes tehina and hummus, a spoonful of amba (a pickled-mango condiment), jalapeños, crisp cucumbers and diced tomato, and an egg that’s been boiled with coffee grounds and onion skins till the whites turn beige.

Like nearly everything we’ve tasted in Israel, each bite is both intensely familiar and entirely novel. It is, indeed, a supremely well-conceived sandwich.

“It’s fucking dope, dude, is what it is!” Solomonov laughs, wiping a smear of tehina from his chin before devouring the rest. •

Guide: Where to Eat in Tel Aviv

Miznon

When Solomonov returns to Israel, his first stop is often at one of the three Tel Aviv branches of this fast-casual pita restaurant from chef Eyal Shani, a local legend here. Jammed from morning to night with a mix of school kids, businessmen, and old neighborhood geezers, Miznon’s flagship on Ibn Gabirol Street comes off like a bunch of teenagers got stoned and opened a pop-up: the stereo blasts hip-hop and Israeli club boomers, the English menu is scribbled on a paper bag, and no one in the kitchen appears to be out of high school. Somehow they manage to turn out the most delicious roasted cauliflower in all of Tel Aviv—and if you’ve never put “delicious” and “cauliflower” in the same sentence, you clearly need to try this. Whole volleyball-sized heads of cauliflower go into the roaring oven for TK# minutes and emerge gorgeously browned and blackened—it looks like burnt brains, and it is brilliant. The consistency is somewhere between a steamed artichoke heart and a hard-boiled egg, the flavor nutty and earthy with a truffle-y punch. You can eat it straight or (Mike’s preference) stuffed into a fluffy pita that’s drizzled with tehina and dressed with cool lettuce, tomato, pickles, and jalapeno. Everything melds together in a soft, creamy mass, bearing the perfect integrity of a drive-thru cheeseburger. Pair it with a side of slow-roasted sweet potato (with a flavor like molasses) and you’ll need nothing else all day. Or at least for another hour.

21 Ibn Gabirol, Tel Aviv, and King George St. 30, Tel Aviv

Busi

Moroccan carrot salad, baba ghannouj, and North African tomato-and-pepper stew are all part of the salatim spread at this 1950s-style grill house.

41 Etzel St., Tel Aviv

Shlomo & Doron

Diners sit shoulder-to-shoulder and use raw onion and warm pita to scoop fresh masabacha hummus at this café near the Carmel Market.

29 Yishkon St., Tel Aviv

Ramleh

Sing and swig vodka alongside dancing Israelis at this popular watering hole, then refuel with grilled sweet apricots served at the bar.

97 Allenby St., Tel Aviv

Carmel Market

Israel’s diversity is on display at this huge emporium: Kiwis, dates, eggplants, pineapples, cukes, and avocados all come from within an hour’s drive.

Allenby, King George, and Sheinkin streets, Tel Aviv

Oved’s Sabich

Unusual sandwiches, like the eggplant pita topped with coffee-and-onion-boiled eggs, are the perfect antidote to a Friday night out.

7 Sirkin St., Givatayim